software for lygia clark

January 24, 2019

January 24, 2019

Art history isn’t exactly a hard science. In a previous life as an art historian it was (or at least I believed it was) my duty to remain as impartial as possible about the work of artists I taught or researched. Obviously, though, I had my favorites. Having never had a chance to write ‘professionally’ about her work as an art historian, I can now write ‘unprofessionally’ about one of my favorite artists - Lygia Clark. I am writing about her not as a professor but as a (mostly) self-taught software engineer, and the distinction matters. As it turns out, these days I turn to Clark’s art for inspiration as often, if not more often, than before.

Lygia’s key lesson for me is about the nature of change itself. As an artist, Clark had a peculiar empathy for change. Her art went through a number of detours away from its modernist roots and towards a wide range of conceptual directions. Many of the core themes in her art surround changes conceptually and in specific - in bodies, places, and objects; across time and space. Beyond her art itself, her life story embodies a remarkable capacity for transformation. Notably, Clark ‘abandoned’ art in the traditional sense in her later years and devoted herself to the kind of therapeutical approach that her art had eventually veered toward.

This particular transition was deeply influential for the world she formally left behind. It has resonated powerfully with me over the last few years, not least in light of my own career transition. Everybody who has been through such a change understands how challenging it can be on multiple levels. This is the case even for those, lucky enough like me, to undertake such transitions by choice, and not out of necessity.

So what is Clark’s art about? Lygia Clark began working in Concrete art, a particularly influential vein of abstract that came to find a home in the cities of her native Brazil around the middle of the twentieth century. Clark’s particular contribution to a collective effort that involved other major figures like Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Pape initially entailed a rejection of a hard-lined approach to abstraction in painting. Instead, she championed a focus on creating objects that not only challenged distinctions between mediums like painting and sculpture, but which also encouraged interaction as opposed to passive contemplation after they were produced.

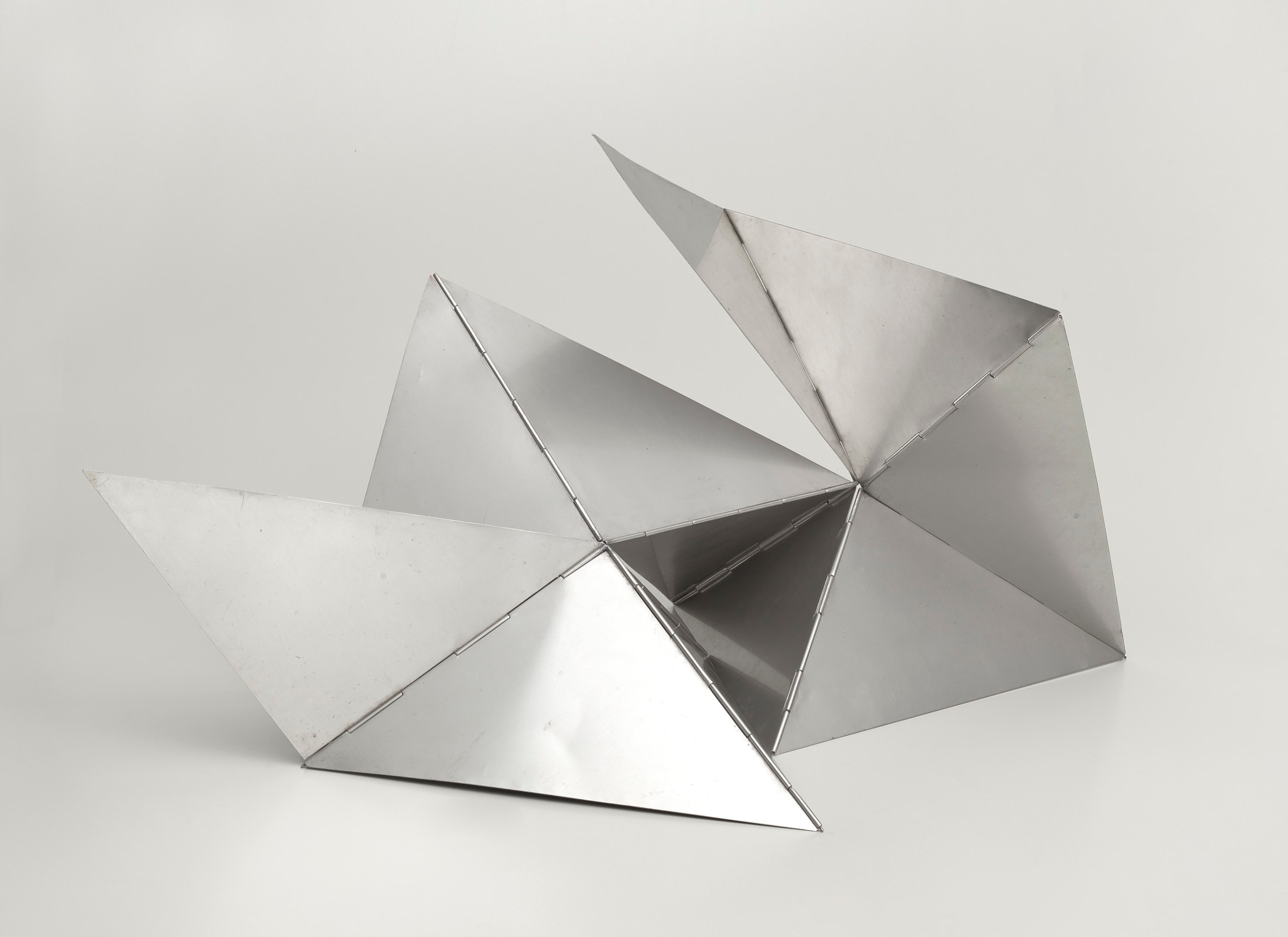

Clark’s Bichos (Critters), for example, are manipulable sculptures built with movable parts. Their forms are mostly geometric, but they encourage a type of playfulness and a potential for direct interaction with their users that painting or sculpture of that time rarely embraced. In contrast to these types of artworks, not only are the materials that bichos are made of (aluminum and similar metals) not all that precious in themselves, their functional focus also differs - they are explicitly meant to be played with, not just looked at.

Eventually, Clark’s interest in this collaborative dimension would become a predominant feature in her art. While it may sound simple enough, this was a massive shift in the direction of art around the middle of the twentieth century.

An early exploration of this idea is her Dialogue of Hands (up, at the beginning of this post). In the work, a white cloth band is turned into a Möbius strip to encircle the wrists of two participants. Far from imprisoning them, the strip is meant to create an intersubjective experience between them that facilitates their communication. Clark believed that such interactions, especially those when subjects were bound to collaborate with each other, could be therapeutic in their own right, and in subsequent years her art become mostly about that pursuit. The aesthetic dimension of her work led to an ever more clearly defined ethical imperative that eventually took over.

Put simply, Clark understood her art as a type of interface - a collaborative space to facilitate and encourage interactions between people. Engineers engage with similar concepts constantly, not just because interfaces are a core part of programming on a conceptual and practical level but because we build things for people collaboratively and, most of the time, to make collaboration among people easier.

Our world is also uniquely defined by constant change. Cycles of obsolescence move particularly fast in software, and the more our products embrace this condition, the better off they are for it. Last but not least, this type of engineering is not a hard science either (many other engineers would debate our calling ourselves engineers, and on many levels, they have a point).

As our systems and products are bound to become parts of an ever-growing ecosystem of products and devices defined by interactions at ever-larger scales, a commitment to making them as ethical and empathetic as possible can potentially make all the difference.